- Home

- Gabriela Harding

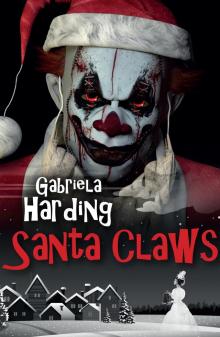

Santa Claws Page 4

Santa Claws Read online

Page 4

“I want an iPad,” said Teddy.

“Teddy, you’re not getting an iPad. You’ll get a broken train like last year,” Honey teased.

“A broken train?” Anaconda took a long, slow sip of her wine. “How quaint.”

“Honey got a doll that laughed in the night. And I got a train with train tracks. But they pinched me so I stopped playing with them.”

“He had to go to the hospital, with the train tracks clamped on his fingers,” Honey explained, lifting Teddy’s scarred thumb. “And the doll didn’t laugh in the night, all right? That was a nightmare!”

“But Honey, I heard her. It was like this: Mua –ha – ha – ha – ha – ha! Mua – ha – ha –ha –ha –ha!”

“Oh dear. You children sure have a vivid imagination. Have you thought of joining the Creative Writing Club? It’s on every Thursday.”

“Neither of you are going anywhere until you can explain this.” Dad was standing white-faced in the doorway. His forehead was sweaty and his eyes livid with fury. On his fingers he rubbed a sort of reddish paste. “Hmm? Well, can you? I found this in the sink. And more of it smeared all over the cabinet. Not hard to realise that my jar of medicine has been fiddled with.”

“You mean, laxative,” said Teddy.

“I.AM.VERY.DISAPOINTED.IN.YOU!”

The children shrunk in their seats. It wasn’t for you, Dad, Honey wanted to scream.

“Go to your rooms. Now. And don’t come out until I tell you to. I want you to reflect on your behaviour.”

“What about our cake?”

“Go to your room, young man! NOW!!”

“It’s all your fault,” Teddy whimpered as they stomped up the stairs. “I told you we’d get into trouble! Now I’m going to bed without cake!”

“Cake? Is that all you think about? Don’t you care that they’re alone down there, free to tell each other secrets we can’t hear? What about that?”

“I don’t care about secrets!” he cried. “I’m hungry! And it’s all your fault!”

“Oh yeah? I don’t remember taking the jar from the bathroom cabinet! And spilling it all over everything! That was what got us into trouble!”

But instead of going to her room, Honey tiptoed to the broom cupboard. The broom cupboard was a box room where all sorts of odd objects were crammed together, stacked on top of each other all the way to the ceiling: brooms, pans, walking sticks, suitcases of all sizes, snowboards, baseball bats, crutches and even a pair of skis. There was just enough room for Honey to crouch down and listen to the conversation downstairs. Through a crack in the floor, she could see a narrow strip of the dinner table.

Dad had put some music on and the symphony crawled upwards, seeping through to Honey’s hiding place. She heard a voice talking over the music. Anaconda was saying something.

“I…must go…no…” was all she could hear.

Yes, she whispered, clenching her fists in the dark. We’ve won! She pressed her cheek to the dusty floor, but the next thing she heard were Dad’s footsteps going out of the dining room. In a panic, she pulled the door shut. The room shuddered with a maddening jingle of objects that threatened to crash into each other. Honey felt something fall from above. It was a book. Mum’s book, she thought with a surge of excitement, seeing the stripy cover. As she opened it she choked out a scream. It wasn’t a book, it was a diary! She turned a page but instead of words she saw stars. Heaps of them. The pain spread rapidly in her skull as a hard thing bounced from her head to the floor. It was a pan, followed by another and then another. The castle of clutter crumbled, burying Honey under a pile of metal, plastic and wood. When the dust cleared, the first thing she saw was Dad standing there, hands on his hips, glaring at her. And behind him was Anaconda, her thin arms coiled like snakes on her chest.

4. Devastating News

Back in her room, Honey breathed at last. It was a miracle that Dad didn’t see the diary. She retrieved it from under her jumper and opened it on her desk. The first page was almost blank, apart from the name Greg Raymond written clearly at the bottom. She had no idea that Dad kept a diary. He just didn’t seem the type. Maybe he was like a painting, too. Maybe he, too, had things hidden beneath the surface. She was about to find out.

Switching on the lamp, she sat down and read a few boring pages. He wrote about the weekend weather or a chess match he’d had with a neighbour, his childhood memories, or a day at work. There was only one word that appeared stubbornly every couple of pages, and that word was Anaconda. She was a bigger part of his life than he’d let on, and Honey felt a surge of panic.

Anaconda made lunch for me today, when she was baking with the children. The pizza was huge and crispy, the most delicious thing, or Anaconda and I stayed late last night to finish the marking or Anaconda insists that she comes over for dinner so she can get to know the children…

‘I knew it!’ Honey cried, relieved. She should have guessed this dinner wasn’t her father’s idea. It couldn’t have been; he loved them, and he still loved their mother, even if… But it was a short-lived relief. She turned the page, and Dad’s last entry stared her in the face, cold as a death sentence.

Friday, 14th December

I haven’t told the children yet, but a holiday has been booked for Anaconda and I on the Isle of Wight. A remote little place, an old-fashioned inn in the middle of nowhere, with no means of communication other than post, which is good, because after everything that happened, I feel I deserve some time for myself. Anaconda has been so good to me that I can’t thank her enough. She is a wonderful woman and I have been thinking lately that I can’t keep living on my own anymore. My daughter is at an age when she needs a mother the most. It breaks my heart to think how much she’s matured during the past months. I talk to her like an adult now and sometimes it dawns on me that she is, after all, only an eleven year old girl who lost her mother.

So, like I said, I have been thinking for some time and made a decision that I’m sure will be in everyone’s best interest: I am going to marry Anaconda. I intend to propose on Christmas Day, when we will both be on the Isle of Wight and the children in London with Flo. The engagement ring that I didn’t get a chance to give Al last year will be Anaconda’s Christmas gift. I know it seems awful to give her a ring that I bought for another woman, but I have been saving for it for so long, and it is such a rare, pink diamond I just can’t bring myself to take it back. And besides, I’m sure Anaconda will never suspect anything about anything. I’ll carry this secret to my grave.

Honey covered her face with her hands. Not only was he going to propose to Miss White but he was leaving them alone for Christmas! Well, Grandma Florence was little more than no company at all. She spoke rotten English, suffered from constant bladder infections (her favourite line was ‘I’ll just quickly pop to the loo’) and was almost senile. Senility is an illness of the old, that makes them all forgetful, so that for instance they forget to dry the laundry before sticking it back in the wardrobe, or they have dog food instead of tinned tuna. In Grandma’s case she often forgot how old they were, and that skipping ropes and marbles were no longer cool presents. But the worst thing about Grandma was not her senility, or her love of alcohol, not even her smelly feet and the hairy mole inside her ear that looked like a horrendous ear plug. The worst, most unforgivable thing about Grandma was her hate for Mum. Every time she came over her parents argued. She remembered eavesdropping on one particular conversation. Both her father and his mother had underestimated her ability to understand French, so they talked without the concern that she might guess what they were saying, while Honey pretended to solve a crossword.

“It’s not so easy to find work in her profession, Flo,” Dad was saying. “Al has been trying, and she most certainly is one amazing chef. An excellent baker. Just the other week the Monsters at number 40 ordered another Black Forest gateau for their daughter’

s graduation. And have you seen the orders she’s stuck on the fridge for the rest of the month? Her cakes are certainly popular.”

Grandma snorted. “Chefing is no profession at all, mon cher. Do you know how they even start off? They scrub dishes until their hands go all crinkly and raw. And, besides, my dear, I have to disagree. Her cooking is absolutely execrable.” She wrinkled her nose. “Not to mention that she is…foreign. That alone is enough to spoil people’s appetite.”

“So are we, Mother!” cried Dad, who only called Grandma Mother when he was furious. “We are French, remember? Stop being racist! Enough is enough.”

“Oui, mon cher, but we are good foreigners,” Grandma had said.

Honey’s cheeks burned with rage.

“There is no such thing, Mother. Good foreigners or bad foreigners…If I had your ideas, I could never teach in a school.”

“Maybe you shouldn’t teach in a school. Teaching is a profession for nerds…”

And it went on.

“Why couldn’t you be clever like Thomas?” Grandma said, not worrying about Dad’s anger any more than she worried about the fact that her granddaughter was sitting on the same sofa as her while she said awful things about her mother. “He is a part-timer. His wife pays all the bills. A clever little thing she is, too.”

“Are you talking about Thomas Lacroix?” Dad sounded amused. “Isn’t he the one who married his mother’s friend? God, Flo, she must be about your age, not that sixty-five is very old, mind.”

Grandma pursed her lips. “All I’m saying is, she could be your mother, too.”

Dad burst out laughing, the wooden queen he was about to move on the chess board between them in midair.

“Who, Al? Sure she could, if she’d had me at four.” He shuffled the queen on the board, flicking Grandma’s knight out of the way. “Check. Your move, Mother.”

But Grandma flounced out of the room, pretending a sudden attack of bulging bladder, knowing that Dad hated nothing more than an abandoned chess match.

As a result, Dad spent the day in a rotten mood and later Honey heard him telling her mother off for rinsing the dishes under the tap.

“Money! Money down the drain!” he shouted.

“But I need to rinse the soap…”

“Rubbish!”

Mum cried herself to sleep in the spare bedroom. This pattern repeated every time Grandma Florence visited. Of course the children disliked her. Actually, dislike wasn’t strong enough a word to describe how they felt about her.

How could he do this? Leave them in the care of a monster, and at Christmas, of all times? He was a horrible father. And how could he say it was in everyone’s best interest? Why, when he clearly only thought about himself! He was a teacher yet he didn’t know a thing about children. How could a stepmother be in a child’s best interest? Every child knows that having a stepmother is worse than having no mother at all. She was never, ever going to forgive him.

Teddy was lying in bed, a pillow over his head, when his sister stormed in. Was he crying? She didn’t care. There was no time for tears now. There were more important things at stake than a lousy piece of cake.

“Get up, Teddy,” she cried, shaking him. “You won’t believe what I found out. Dad’s going to marry Miss White! We’re going to have a snake for a mother!”

Teddy jumped up.

“What? How do you know?”

“I found Dad’s diary.” She threw the book down on the bed. “He’s giving her Mum’s ring for Christmas and we’ll be home alone with Grandma Florence!”

“What ring? What are you talking about?” said Teddy, flicking through the pages of the diary. “Oh, look! A lock of her hair!” He pulled out a glossy black plait tied with a mauve ribbon.

“Eeew!” Honey held the hair at arm’s length by a thread that had come loose on the ribbon.

“Disgusting!” Teddy agreed.

Sniggering, she let the tuft of alien hair fall on her brother. He brushed it away, screaming.

“Listen now,” Honey dropped her voice, peeking around the door to make sure no one was listening. From downstairs she heard voices and something that sounded like muffled kisses, then the slam of the front door. A car engine roared. She’s gone, Honey thought, relieved. She took a deep breath, turning to face her brother. “Daddy bought this amazing ring for Mum last year, an engagement ring, but she…she wasn’t here to open her presents.” She swallowed. Why couldn’t she say the word? Why couldn’t she just admit that Mum…

“An engagement ring?” Teddy stroked Kitty, who had squeezed out from between a couple of shoe boxes under the bed and leapt into his lap.

“Yes, silly. That’s what people do when they want to get married. Don’t ask me why.”

“I thought Mum and Dad were married.”

“Well, they were…in a way…but not really. It’s hard to explain. They were rehearsing for the big show. But now there’s not going to be a show, because Mum is gone and Miss White took her place. And she’s going to act in the show, even if she’s a fraud, and doesn’t…”

Teddy shook his head. “I don’t get this.”

“We need a plan,” sighed Honey. “Think of something if you don’t want Grandma to cook you in the oven instead of the turkey because she’s too drunk to tell the difference.”

“What do you mean he’s giving her a ring for Christmas? Is it her birthday or something? At Christmas? And if they’re going away, how will Santa know where to leave their presents?”

Honey rolled her eyes.

“Look, Teddy, there is no easy way to say this but Santa Claus doesn’t exist. Ok? I’ve said it. I can’t believe you still think Santa is real – I mean, you’re eight!”

“I’m not eight.”

“Ok, seven and a half. Still, it’s about time you found out. I’ve known for a while now and it seems unfair not to tell you…I mean, isn’t it obvious?” She sighed. “The thing is, Santa Claus is…Dad. And Mum, when she was here. What I mean is, they sneak downstairs in the middle of the night while we are asleep and leave the presents under the tree. That’s all there is to it. There’s no magic or anything. All adults are liars, every one of them.”

Teddy shook his head. “I don’t believe it. Of course there’s magic. I have seeds that can make apple trees. You just need water and a spell.”

“That’s not magic, that’s just…nature. Anyway, I bet you £50 that there is no Santa Claus. I think I can find a way to prove it to you. Deal?”

“You don’t have £50,” Teddy said.

“That’s exactly my point. I won’t need it.”

The next few days flew by. It was getting colder. Every morning the park was covered in a fresh coat of white frost growing thicker by the hour. The wind brought snowflakes to the garden: they whirled by, lighter than the air, clinging to the leaves of the magnolia tree like dandelion fluffs. Kitty, thinking they were butterflies, stood watching them with her tail twitching from side to side, her paw reaching out for them and coming back empty. Squirrels skittered about like bouncy balls of fur, looking for acorns. Nothing, not even the green rubbish bins, escaped their search for food.

The children were room-bound for four days before they were even allowed to come down to the kitchen. They didn’t remember Dad ever being that strict before but, he said, what they did was more serious than anything they’d done in the past. Revoltingly, he never once asked them why they did it. That would have been a sensible question. The reason he didn’t, Honey thought, was that he already knew. They would never approve of Miss White. It wasn’t a secret she was in love with him. It was plain obvious. Even Mum used to tease him about it. One night they were having dinner together when Miss White phoned to discuss something about work. It was Mum who picked up the phone. Honey smiled as she recalled that particular conversation.

Everyone knew, apart from Dad, of course. To think he was a chess champion! How could someone be so clever and so dumb at the same time? It made Honey angry to know that Miss White was finally going to have her way. She had been racking her brains to find a plan but, without books, she was totally out of fuel. All her brilliant ideas had been inspired by novels. Without books, she was like a prisoner locked in a dark cell. Totally powerless.

From her window she could see the rooftop of the local library. Closing her eyes, she searched through her memory for the smell she knew all so well: the smell of old paper and dust, mingled with the aroma of freshly brewed coffee and warm croissants wafting from the small cafeteria in the corner. She’d sat there many times in the last months, looking through the pages of one book or another, unable to decide which two to take home. Her last book had been a novel by Anna Jacobs. She read it with her English Thesaurus, opening it every now and then to look for words she didn’t understand. It was a grown-up book but she loved it nonetheless.

A knock on the door disturbed her thoughts. It could only be Dad. He had taken to knocking on her door now rather than barge in like before. Teddy didn’t mind but she was eleven years old – hardly a child anymore. Deep down in her heart, she felt much older than that.

“Yes, Dad.”

He opened the door and walked in, wearing a hooded anorak and his dirty trainers. They squeaked and squelched as he strode along, crossing Honey’s kingdom. Her bedroom was the widest room in Chess Cottage. She frowned. Mum would have a heart attack if she saw him trampling around the house with his mucky shoes on.

“Fancy going out for lunch? I was thinking we could go to the Swan and Duckling, the new pub in Ealing. Apparently it’s really good, child friendly and…”

Santa Claws

Santa Claws