- Home

- Gabriela Harding

Santa Claws Page 2

Santa Claws Read online

Page 2

“Gherkin stew?!!” Honey screamed, unclipping the peg from her nose. Within seconds, she was relieved to hear Dad’s nerdy laughter.

“Just joking, puppet. I’ve made pepperoni pizza with garlic bread and organic rocket salad! Voilá!” He pointed to the oven. “Ready in five!”

Honey’s stomach turned upside down. She was as sick of frozen dinners as she was of living a dull, uneventful life. You didn’t exactly make it, she wanted to say. You just stuck it in the oven. They’d been eating fish cakes and pizza with garlic bread and very little else for a year now. Fine cuisine was not one of Dad’s strengths. That was funny, considering he was French. Some of the world’s best chefs were French.

She’d always taken her mother’s cooking for granted. The spicy enchiladas with sour cream, coq au vin, moussaka, crispy ducklings, paella and all the lovely curries. Exquisite dishes even if in those days she longed for chicken and chips or hamburgers. Her mother’s meals were like plays, gradually served in acts, unexpected, always with a hint of suspense because you never knew what was the pièce de résistance, the most exciting dish of the night. It could be a cake made to look like an egg or a wonderful sugar apple. It could be the face of a clown drawn with pickled red peppers on a boeuf salad dressed with mayonnaise. Or a miniature dollhouse made entirely of gingerbread. They were plays with happy endings, fantastic desserts served on immaculate square plates. All those plates had been stored away on some dusty shelf in the kitchen. With Dad it was always a chocolate bar or boring fruit preserves.

Her mother believed in happy endings and the supremacy of good over evil. She was always so positive. It was ironic that their life together had been so short and had such a sad ending. This time last year she couldn’t imagine her life without Mum. Now she couldn’t imagine how it would be to have Mum in her life again. There was one thing she was sure of – it would never be the same.

Up on the wall, Mum’s collection of Shogun knives – the biggest one looking like a Samurai sword and the littlest no bigger than her thumb – seemed to smile at her. The littlest knife was missing; it had been missing ever since. In its place was a fine layer of golden dust.

***

“So,” Dad said, while cutting his pizza ever so neatly with a knife and fork. “How was school?”

“Dad, we broke up yesterday. We’re at home today. You took the day off to look after us. And make pickles,” Honey added sarcastically. She rolled her eyes, not hiding her contempt at her father’s lack of concentration.

She folded her pizza in two and took a savage bite that sprayed ketchup all over the tablecloth. She wiped her mouth with her sleeve and wiped her sleeve on the front of her top. Dad didn’t seem to notice.

“I took the day off because I have a cold,” he said, sniffling loudly.

Honey and Teddy exchanged a look. She could tell her little brother was enjoying his pizza, grateful to have a dad who couldn’t care less about healthy eating. He was still not old enough to appreciate good food – apart from cakes, of course.

“Today was a training day at school,” said Dad. “Nothing exciting. Just a bunch of dull people teaching teachers how to look after children like you. Dull, really.”

Well, you could do with some advice on that, thought Honey, glaring at him over the burnt edge of her pizza.

“How is Miss White, Dad? Did you see her yesterday?” she heard Teddy say.

Honey grinned. Dad turned the colour of the pickled red peppers on the shelf behind him.

“I did actually. She was asking about you two. She said hello.”

Honey and Teddy looked at each other and then back at their father, who was looking down at his plate.

“Actually… there is something I need to talk to you about. Something I’d like to ask your opinion about.” He cleared his throat, folding and unfolding a kitchen towel on his knees. “It’s…it’s about Miss White. I’ve invited her to have dinner with us tomorrow night. I hope that’s OK.”

Sweat beads popped on Dad’s forehead. He was just an ordinary adult, pretending to ask when in fact he was telling. What if they said no? Would he go back on his word and tell Miss White not to come? Certainly not. Just like any other adult in the world, he didn’t think a child’s opinion was that important. After all, if the world thought children were important, they would give them more power. Why, they were little more than household slaves. Obeying rules. Begging for money. Not having a say. The world was pathetic.

But, there was still hope. If Miss White got to taste Dad’s cooking, she was sure to run a mile! Or, if they were lucky, she would get food poisoning and be off from work so that she couldn’t chase Dad around with cups of tea and Celebration chocolates. Yes, that was it. They had to somehow get to her food. Then Honey had a brilliant idea. She remembered the jar of laxative jam in the bathroom cabinet. Oh, wasn’t she a genius! She got up and began clearing the table, smiling from ear to ear.

“Dad, I think that’s a very good idea.”

2. Call Me Anaconda

The day broke, raw and glossy, like a snake shedding its skin. Fallen leaves in the park were crisp with frost. There was ice dust on the empty benches and the playground looked desolate with no children rocking in swings or gliding down the slides. They were all tucked away in their beds with their soft toys, dreaming blissful dreams of angels, chocolate and reindeers. It was almost Christmas and the festive mood had enveloped the entire town of Hanwell. Windows were decorated with lights and candles, and Christmas trees already glowed behind polished panes of glass. On Christmas Eve snow was forecasted and small children who had never seen snow before slipped this wish into their prayers: Let it snow, let it snow, let it snow. It was like casting a spell. All the children secretly believed in magic. And it wasn’t a secret that magic worked only for those who believed in it.

House number 6 on Cuckoo Lane was asleep behind bushes of butter-shade roses. All the lights were off, the windows shut. A film of thin ice weaved from leaf to leaf in the frozen shrubs. The only signs of life were the blackbirds whooshing from one windowsill to the next, in search of breadcrumbs. They always took their breakfast early and it was known that Chess Cottage provided the richest, most varied, all-you-can-eat breakfast for miles around. In the end they settled on the bird feeders, eating under the eyes of the famished squirrels.

***

Honey was awoken by the sound of her own scream. Dad had been kneeling on the landing, sliding something through the cat flap. Why was there a cat flap in the bathroom door? A train whistled in the distance; the floor shuddered; through an open bedroom window with a billowing curtain Honey saw the bridge collapsing in a pile of rubble. Don’t ever go near that bridge…A damp, bloody hand reached out through the cat flap. Honey gasped. Dad slowly looked up, drawing nearer and nearer to where Honey stood petrified. There was something strange about the way he moved. The house opened under her; a zigzag crack spread over the hall, ripping the carpet, revealing the mahogany floors beneath…Dad’s pupils were enlarged as he watched her falling. And suddenly she was back in her room, taking large gulps from the strawberry-scented air.

She leapt out of bed and pulled down the window. The bright sun filled the room with speckles of emerald green. She closed her eyes, breathing into the cool breeze.

After changing into a pair of jeans and a turtleneck jumper, she tied her hair back without bothering to brush it. She slid down the banister. The entrance hall was silent, the mirror reflecting the umbrella stand and the hat stand, the door to the cellar firmly closed, as it had been for the last year. No one went in there anymore. As in a dream, Honey heard for a moment the reassuring buzz of the wheel where Mum cut all their keys. She could almost see Mum there, surrounded by all her locksmith’s tools. The cellar was her universe, a place where she sat fixing things and writing novels.

A knock on the door startled her. She whirled around, but

couldn’t see anything behind the stained glass, apart from the monotonous rain falling from an overcast sky. She heard the dull sound it made as it slapped the flagstones.

It was then, when she considered stepping out into the rain to catch whoever had knocked on the door and ran away, that she realised the black umbrella was missing. It was Dad’s favourite – a sleek, black thing with an elegant curved handle and a button that made the soft, waterproof fabric flick open like the wings of a giant bird. It had a long, pointy top that Dad used to tap the stones in the pavement with, one by one, as if he was playing some kind of childish game.

It was missing. And now, come to think of it, it had been missing for some time. But, weirdest thing of all, Dad hadn’t said a word about it. Was it possible to be so distracted that you don’t notice your favourite umbrella is missing, in a city where it rains almost every day?

Honey stepped out into the rain, barefoot and holding one of the shabby umbrellas from the bottom of the stand. She looked up and down the street, shivering against the chilly wind. A fox crawled out of some bushes and looked straight at her with yellow, mournful eyes. Back inside, she was surprised to see the newspaper lying on the rug by the door. It was only the postman, Honey thought, and made her way to the kitchen.

The table was still stained with ketchup from last night’s supper and there were pizza crumbs and rocket leaves on the pawn chairs and down on the chess board floor. Honey picked up a dust pan and broom, swept and mopped the floor, carefully placed all the bits of card in a box labelled ‘Paper and Card’ to be recycled on Wednesday morning. She chucked the rocket leaves in the green bag over carrot and potato peels, and turned her nose up at a new box containing egg shells. There was another one right next to it, full of used coffee beans. Yuck. In just one year, this kitchen had transformed from a food paradise into a rubbish dump. The recycle bags filled slowly. They stank. She wished she could just chuck everything in the bin, like Mum did, but she couldn’t do that to Dad.

Climbing on a pawn chair, Honey opened the highest cupboard over the microwave and removed a Fairy capsule from a green bag. She snorted as she placed it in the dishwasher, thinking Dad ought to realise that Teddy and herself weren’t likely to mistake Fairy tablets for jelly beans anymore, and, as the machine whirred into life, she threw a couple of crumpets in the toaster and made a mug of hazelnut cappuccino. She wasn’t allowed it, but Dad didn’t notice anything these days. He hardly even noticed his own children. She wondered how long it would take him to miss them if they ran away.

She carried the breakfast tray to the lounge, sank into the settee and started looking through the paper.

It was a habit she’d taken to recently, reading the paper. Maybe it was because she was always short of books. When she asked Dad to get her some more, he suggested she should get rid of some of the beautiful novels that stacked on her shelves.

“What?” Honey cried, in disbelief. “Why would I do something like that?”

“So we can replace them with new ones, of course. I mean, what’s the point of keeping books you’ve already read? I like to keep a clean house.”

Honey was mortified. Getting rid of books you loved! It was like sending your children to an orphanage or sentencing your pets to death. It was unthinkable.

“Why don’t you get rid of your chess boards, then? You must have at least ten of them, lying all over the house. I mean, you already used them, didn’t you? So what’s the point of keeping them?”

“Don’t argue with me, young lady. Chess boards and books are not the same thing.”

She disagreed. Chess boards and books were the same. They both fell into the same category of objects loved by people. But Dad didn’t seem to get that. This was another thing about adults: they didn’t notice the obvious. They just questioned too much. She never used to question anything before. Now, she questioned everything. Was she turning into an adult, too?

There was nothing left on her plate but a golden pool of butter when she realised her cappuccino was cold. She picked up her mug and strolled over to the kitchen. As she poured milk over her drink she noticed the photograph on the carton. It was a little boy’s face, smiling above a few rows of black writing. Honey scanned the words. Jerry…reward…disappeared…So, another missing child. This was one of the children who disappeared without trace last Christmas. They were never found, dead or alive. Since then, security had been reinforced in schools, and the teachers insisted that children be picked up by parents only, even those who were normally allowed to walk home by themselves. Although, strangely, all these children had disappeared from their homes…

Honey pressed a few buttons on the microwave. The lights turned on and the mug went round in circles like the ballerina in her music box. The soft buzzing sound brought back a disturbing thought she’d tried to brush aside. She opened the door, grabbed the mug and slammed it down. No! There are no tooth fairies. No Santa. No wizards. No good and evil. No God. And certainly, no living dolls.

Teddy was playing on his iPhone and Honey was busy reading a book on marriage rituals – she had just finished a chapter on Fraternal Polyandry – when Dad returned from the supermarket. The children couldn’t be persuaded to go with him, knowing he was shopping for the dreaded dinner. Besides, the only thing they needed was in the downstairs bathroom, up on the second shelf of the medicine cabinet.

“Teddy,” Honey nudged her brother, giggling uncontrollably. She showed him a picture of a woman, three men and two children posing against a backdrop of blue mountains and valleys. “Did you know that in some parts of the world, a woman can marry up to seven brothers? Brothers can marry the same wife!”

“Eeew, gross!” Teddy screwed up his face, grabbing the book. “Like, when I have a wife, she can marry you too?”

“No, no!” Honey almost rolled off the sofa in a fit of laughter. “Not sisters – brothers!”

“Why don’t they marry a wife each?” he asked, squinting at the faded photos.

“It depends on the region,” explained Honey, importantly. “In Tibet, which is in China –”

“I know where Tibet is,” Teddy interrupted.

“I know you know. So, in Tibet, it was popular among poor farmers because they didn’t want to divide their property. It is also practised among the Nayar people of Southern India, and some North American Indian and Eskimo societies, generally in families where there’s a shortage of women or it’s difficult to support a family.”

“I don’t think it’s true.”

“It is true.”

“Then I’m glad I’m not a Nayar and I don’t have a brother!”

They chuckled, then their attention returned to the plan they had made.

While Dad was away, Honey told Teddy about her idea. She had to show him what laxative meant in the English Thesaurus Dictionary that she used for her crosswords: Laxative is a medicine tending to stimulate or facilitate evacuation of the bowels. Still, he didn’t understand until she gave him a matter-of-fact explanation. He chortled at the idea of having their guest spending the night on the toilet.

“Awesome! But if Dad finds out, we’re in trouble.”

“He won’t,” his sister reassured him. “He’ll just think she’s a disgusting old woman farting at dinner!”

Teddy roared with laughter. He had never liked Miss White. She confiscated the dried apple seeds that he stored in his tray at school, saying the tray was for books only, not clutter. But those seeds were magic: they could make trees. Seventy two seeds, collected over weeks of digging them out of apple cores, gone in one shake of the tray into the rubbish bin.

“I’m home!”

They heard the rustle of shopping bags and the heavy stomping of Dad’s winter boots in the hallway. They listened as he left the bags at the foot of the stairs and went back to the car for the next load. In total, they counted three trips back to t

he car. He had certainly been in a shopping mood.

“Crikey! It’s dark in here. Anyone fancy helping me make supper?” he said, popping his head around the door and flicking on the lights.

“You mean, turn the oven on or set the table or something?” Honey replied, turning a page of her book. Teddy groaned as another angry bird on his phone flew out of reach.

“Ha ha. Very funny. Look, I’m laughing.” He sat down to unlace his boots. “Tonight I’m making turkey with cranberry sauce, roasted potatoes and greens. For dessert I will be serving my very own sponge cake.”

“Wicked!” Teddy’s eyes lit up at the mention of cake.

My, my, thought Honey, chewing a handful of peanuts. You really are head over heels. Let’s see if you’ll still feel the same after tonight…

“I’ll help, Dad,” she said gleefully. “I’ll make the cranberry sauce, if you want. And I can mix the butter and flour for the cake.”

Dad looked relieved. “Good. I thought I was on my own here. We have exactly…three hours to go.”

The three Raymonds glanced at the big, horse-shaped clock. They all had the same wish: for the hours to go by quickly and for everything to go well tonight. Well, however, was a relative matter.

The bird was roasting in the oven and Teddy was snapping asparagus heads, wearing washing up gloves so that the sticky sap would not get on his fingers, when Honey took out the snow white, embroidered tablecloth reserved for special occasions and spread it over the round kitchen table.

“We’re eating in the dining room,” Dad announced importantly, wiping his hands on his apron. “What, did you really think we would receive a guest in this kitchen?” He gestured to the spilled coffee on the worktop, the stained walls, the spider drowned in a puddle of soup on the greasy cooker.

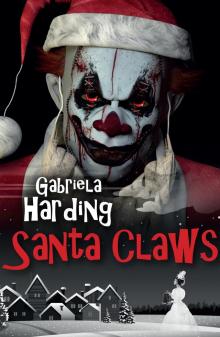

Santa Claws

Santa Claws